The Narwhals’ Tale of Rising Seawater and Sinking Ocean

Part 1, Warming Ocean and Climate Change

There has been much discussion on how Climate Change impacts the ocean. Researchers in Baffin Bay found proof of how the ocean takes up excess heat from the atmosphere by working with the resident whales, the narwhals.

Narwhals, speckled blackish-brown over a white background, becoming whiter with age, are 13 to 18 feet long from head to flukes. There is no dorsal fin. The neck of the narwhal differs from most other whales. Like land mammals, the neck vertebrae are jointed, not fused. The shape of tail flukes differs between females and males. Female whales have flukes similar to dolphins, and the leading edge sweeps back to join the trailing edge obliquely in a more triangle-shaped shape. The male narwhal tail has more of a mustache shape. From the “small” where the tail meets the body, the leading edge is more concaved, dipping back and out.

Jointed vertebrae and fluke hydrodynamics have evolved for male narwhals to carry a five to ten-foot-long tusk that erupts through the lip on the left side of the upper jaw. What was once a canine tooth has become a most remarkable left-handed helix spiral. Millions of nerve endings in the tusk connect seawater stimuli with the narwhal’s brain. Rubbing tusks together with male narwhals are thought to communicate the water characteristics each has experienced.

Narwhals may converse about water much like people talk of fine wines. Fourteen narwhals in Baffin Bay wearing sensor tags will tell us, later in this article, something about how climate change affects the seawater that flows into the Gulf of Maine.

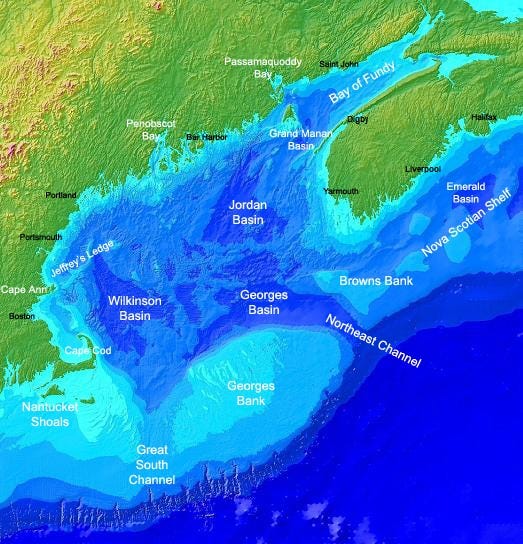

Conversations in Boston and Portsmouth on climate change impacts on the ocean have escalated to swagger. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than any other water body in the world, and our waters are in the worst condition and worsening faster than others, they say.

The belief that one’s local ocean water body is warming faster than the rest of the ocean came suddenly, turned on like a light switch groped in the dark, by a single science journal publication splashed by the media. I was stunned to hear individuals who have spent much time on the ocean say something contrary to their own observations and personal experiences.

Concerns of being the frogs worse off in a stovetop kettle arose from a report in a science journal. The findings boiled down to two sentences that gave alarm to the discussions that followed. “Between 2004 and 2013, the mean surface temperature of the Gulf of Maine rose a remarkable 4°F.” Last year’s “rise in temperature exceeded those found in 99 percent of the world’s other large bodies of saltwater.” The authors were quick to conclude that the rapid warming of surface seawater due to global warming led to the collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery.

Perhaps there was too much deconstruction of marine ecosystems, too much simplifying down to one easily measured factor, temperature, that would tell all one needs to know. The challenge was to reconcile what the authors claimed with basic understandings gained through experience of the workings of oceans.

A whale watch narrator out on Stellwagen Bank explained global warming like a blanket on the water warming it. Inferred was that this bit of ocean is warming faster than in other ocean places because there is a thicker blanket of greenhouse gasses here than elsewhere. I got an image of the world wrapped in a patchwork quilt of varying thicknesses, and unfortunately, we got a thick patch.

Not so; the greenhouse gasses of climate change are not substantially thicker on some water bodies than others. The winds blow around the world; they vary and change when land surfaces rise and fall and warm and cool. The air molecules are redistributed evenly in the atmosphere. Some of the air we breathe was once air in China. Climate change carbon measurements are taken far from smog and smokestacks. The first observations were made on Mauna Loa, Hawaii. Barrow, Alaska followed. Today, American measurements of carbon in the atmosphere are also recorded in American Samoa and at McMurdo Station, Antarctica.

There is some regional variation. The U.S. East Coast was recently reported to have 412 parts per million of carbon, slightly less than the North Pole (421 ppm CO2) and a bit more than the South Coast of England (394 ppm CO2).

At the science café in the basement of the Portsmouth Brewery, a marine biology graduate student studying lobsters said the surface waters of the Gulf of Maine were warming faster than anywhere else. I said it is a good thing lobsters don’t live in the surface waters. No, was the reply. They can correlate surface water temperature with temperatures all the way down to the ocean floor.

He talked about how lobsters in the Gulf of Maine were being landed in record numbers while lobster populations south of Cape Cod were crashing to record lows. To the south, rising temperatures have been wreaking havoc to lobsters. How could the Ph.D. student, who knows the life of lobsters in cool and warmer waters, believe the Gulf of Maine water body is warming faster than anywhere else when these lobsters show no signs of heat stress?

Lobster boats out of Martha’s Vineyard must carry a vat of boiling water in the back of the vessel. The pots are dunked into the bath to rid traps of 30 to 40 pounds of algae before being set again. Lobstermen hold the nutrients from lush green lawns of waterfront estates responsible for making their lives difficult.

Three factors control algal blooms: daylight length, temperature, and nutrients. The worst algal blooms occur during the summer when daylight is most extended, the water is warmest, and nutrient runoff or upwelling is the greatest. Warm water holds less oxygen than cold water. Algae can grow and die so rapidly that oxygen is used up, and this place becomes an ocean-dead zone. Striped bass have been observed chasing bait fish. Suddenly, all the fish roll over dead, having swum into an ocean-dead zone.

The whale watch narrator and graduate student stretched their explanations to reconcile the incongruities of the claim trumpeted by the media. We defer and accept without question the conclusion of a reputable science article out of respect and because we want to be part of the “scientific community," especially when it confirms something difficult to experience first-hand but no less real: Climate Change.

Next: Part 2. Pint Glass With Ice Debunks Reports of Atlantic Ocean Current Collapse

Excellent article, Rob. I learned a lot and am looking forward to your next post. Thankyou.