Pint Glass With Ice Debunks Reports of Atlantic Ocean Current Collapse

Part 2. The Narwhals' Tale of Rising Seawater and Sinking Ocean

There was no ambiguity to the title of the juried science journal article: “Warning of a forthcoming collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation.” Any year within this century, ocean currents will completely stop if we continue to emit the same level of greenhouse gasses as we do today. When the movement of the Atlantic Ocean ceases, it will become too cold north of London for trees to grow, and equatorial latitudes, including Florida, will sizzle.

A close read of this article reveals that “indications” that “suggest” ocean currents shift slightly in intensity have been found. Both weaker or more substantial are reported. It sounds more like speculation than science. The slight shifts in water flow are the amount of flow the Gulf Stream varies seasonally as it meanders northwards. Flowing at the strength of six hundred Amazon Rivers, scientists believe that it will be slowed by all the meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Arctic Ocean. They call it “freshwater forcing.” But they are at a loss to explain how a stream has ever been slowed by adding more water.

The Arctic Ocean sea ice has melted back, revealing more of the ocean than in decades past. It freezes entirely in October, and the melted water stays in the Arctic. Climate Change has brought longer, hotter summers to Greenland. Shallowing windrows of meltwater cover the Ice Sheet. It is unknown how much water returns to ice, whether more or less than 50% refreezes.

The meltwater volume is daunting because people do not know Greenland's size. Enough meltwater to cover California four feet deep is impressive. Greenland, at 836330 square miles, could contain five Californias and two New Jerseys with 350 square miles to spare. Greenland’s green landscape is larger than that of California. With plenty of water and longer, hotter summers, plants are photosynthesizing more and storing more carbon in biomass. As a result, no increase in meltwater reaching the sea has been observed, and there is no freshwater puddling on the ocean surface.

People know their places through experience, both at sea and on land. Spin fiction posing as fact with threats of apocalyptic tipping points undermines the science and our work to address climate change and restore the imbalances we have upset.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is part of the world’s ocean current. It begins in the Greenland Sea north of Iceland, travels around the Atlantic into the Pacific, onto the Indian Ocean around the Antarctic continent, and back to a counterclockwise turn around the Atlantic Ocean, past Norway, into the Arctic Ocean. Once around the Arctic Ocean, it bears right before the circulation is completed southbound in the Greenland Sea. A bucket of seawater poured into the Greenland Sea will take about 1,600 years to circulate.

Wallace S. Broecker first described the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt that wraps around the world. His discovery came after several decades of tracing the routes and using radioisotopes to date the age of deep waters. Ocean circulation determines local climates. The world turns to the East, causing equatorial ocean currents to flow West and to bend to the right, driving the Gulf Stream north to warm Britain and Scandinavia. In the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland, cold nutrient-rich water from the Arctic Ocean meets and dives 11,000 feet below warm nutrient-Atlantic water. The East Greenland Current bears right around Cape Farewell to flow north by West Greenland into Baffin Bay and south back into the Labrador Sea between Greenland and Labrador. The Labrador Current, strengthened by water from Hudson Bay, cools Newfoundland and New England.

Broecker’s interests in connections between the ocean and atmosphere were heightened when ice cores from Greenland indicated 25 climate changes during the ice ages of the last 150 million years. The abrupt switching between the ice age and warming conditions, a difference of 11 to 15 degrees Celsius, happened over many decades if not centuries. Research of foraminifera in deep ocean sediments found concurrent stop-and-go action to the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt. The quest for what caused climatic switches is on. All eyes now turn to the Greenland Sea as we seek to understand the phenomena that turn on or off the ocean circulation and global climates.

Scientists warn that ocean circulation may cease within the century. They base their conclusion on some sparse measurements in the Greenland Sea collected over seven years. They say the sea surface temperatures are “fingerprints testifying to the strength of the AMOC.”

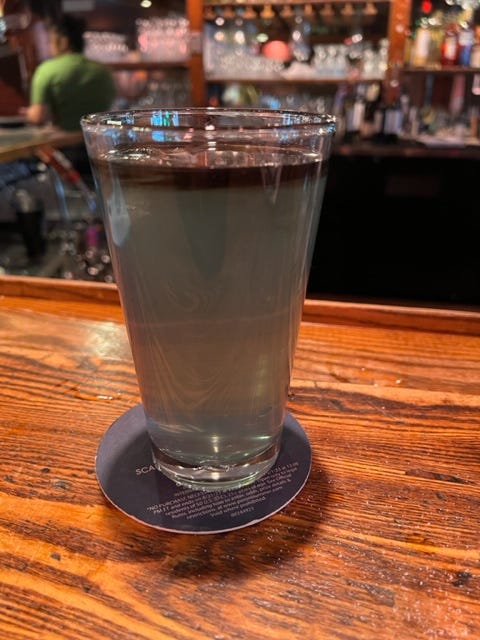

With a pint glass of tap water, we can test for surface water fingerprints and what drives the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt around the world. A tablespoon of salt mixed into a pint of water is 40 parts per thousand of salt. This is the saltiness of the Mediterranean Sea. It is higher than the Atlantic Ocean, which is 36 ppt. The Gulf of Maine, a sea beside the Atlantic Ocean, is less salty at 34 ppt due to all of the freshwater warmed by the land that enters from rivers.

Wallace Broecker observed that the Atlantic Ocean's salinity should be 35 ppt, except evaporation raised it to 36 ppt. He postulated that a warming sea might have more evaporation, denser water due to higher salinity, and stronger ocean currents.

Place an ice cube into the glass of briny water that is no longer circulating from the stirred salt. Drip a drop or two of food coloring onto the ice cube. The color will pool on the cube and then slide off with the meltwater to spread out on top of the salt water. Density is both temperature and salinity. Although cold water is denser than hot water, freshwater forms a black band on top of salt water.

Note: The food coloring was added here while the water was spinning after mixing in the salt. This pulled some of the black meltwater into the briny deep. Thanks to Rim at Grendel’s Den, Harvard Square, for tending the bar.

There are no fingerprints here because waterbodies, defined by temperature and salinity, stay independent and can travel in their own directions. The southbound Labrador Current flows easily beneath the Gulf Stream. Further north, where the Gulf Stream warms Ireland and Scotland’s Hebrides Islands, the Labrador Current off Newfoundland brings cold weather and once delivered an iceberg to the Titanic.

A patch of fresh water on top of salt water is known to dingy sailors racing around a course as a “slippery sea.” Tidal currents move one way, while the lens of less dense pushed by the wind may slide in a different direction and speed. Sea-savvy sailors win more races.

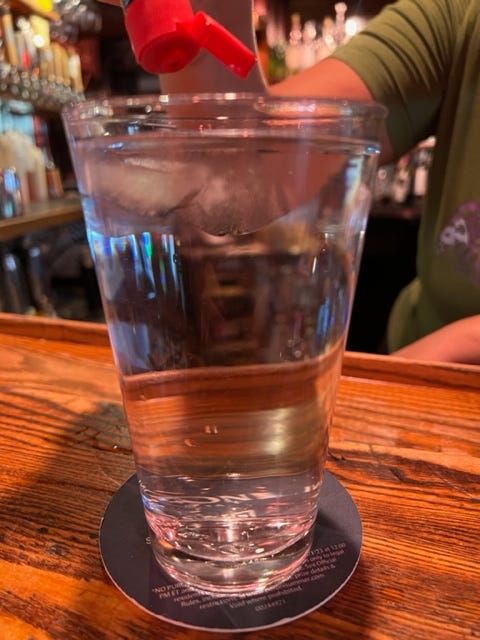

Let’s take another glass to compare the two water bodies in a pint glass. Add an ice cube to a pint of fresh water.

Drip the food coloring on the berg, watch the colored icy water cascade to the bottom, and feather out laterally. Cold water is denser than warm water and sinks.

When the fronds of colored water warm to the temperature of the surrounding water, the water will mix thoroughly to be one color.

Photo: Outside, the pint glass on the left contains salt water below, blue freshwater above, and an ice cube. The pint glass on the right is fresh water, and the ice cube has melted away. The white tent overhead is reflected in the freshwater glass’s surface to look like ice.

Touch the freshwater pint glass and feel the temperature. Compare this to the saltwater body in the other glass. Which one is warmer? Touch the colored water on top of the salt water. This water body may be so much colder that condensation will likely form outside the glass. The ice cube in freshwater has entirely melted away, while in the water body above saltwater, the ice cube survives (much to the distress of the Titanic). The temperature of surface water has no relationship to the temperature below.

The Great Ocean Conveyor Belt may remind you of a cafeteria where trays of dirty dishes are placed on a belt to “ensure” they are “connected” to the dishwasher. In the ocean, the sinking of cold, dense water powers ocean circulation. The Earth’s rotation has set up the direction of flow that is strengthened by thermohaline circulation.

The Svalbard archipelago on the threshold between the Atlantic and the Arctic Oceans is the other end of the transport of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. In 2007, warm Atlantic water surfaced in Svalbard to cause glaciers to melt on the islands. With the Gulf Stream flowing stronger, more warm water is going into the Arctic Ocean beneath the surface water body. This is why the sea ice melted back, exposing more open water than atmospheric scientists had expected. They could not see beneath the ocean’s surface (or read reports from Svalbard).

An indication of a stronger flow for a more robust AMOC was observed in 2011 when the Gulf Stream meandered up onto the continental shelf closer to Rhode Island than ever recorded before. Rivers meander to dissipate energy. The Gulf Stream must dissipate energy by meandering after squeezing through the Florida Straits between Florida and the Bahamas.

The Gulf Stream jets through the Florida Straits at a clip of 28-32 Sverdrups with a seasonal variation of 3.5 Sverdrups. A Sverdrup equals 1 million cubic meters per second, or the flow of five Amazon Rivers—all the rivers in the world discharge about 1.2 Sverdrups into the ocean. Flooding northwards, the Gulf Stream picks up water. When the Gulf Stream is East of New England, the mighty current moves at 150 Sverdrups per second or about 700 Amazon Rivers. Greenland meltwater and greenhouse gases will not be slowing down this freight train.

Raise a glass to the health of the ocean. The immensity and power are beyond comprehension by all but the most experienced seamen humbled by it. However, we know a pint glass and can see how a slippery puddle of fresh water can do nothing to the briny deep. With fresh meltwater sitting on salty, warm water, we know the ocean is not a bathtub where one can check the water temperature with a toe. The sea is deep, with layers of water bodies defined by thermohaline density moving in different directions at different speeds. Don’t judge an ocean by its surface; underestimate it at your peril.