The long, hard slog through winter carries on for those of us up north, but the sweet beginnings of spring are not far off.

Now is a great time to take part in the revival of an old practice that's gaining new momentum: planting trees for shelterbelts, windbreaks, or even just shade!

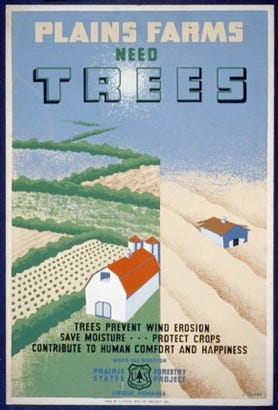

Shelterbelts, or windbreaks, are rows of trees strategically planted along one or more sides of crops, fields, homes, or on public lands for a variety of environmental and economic benefits.

During the 1930s, the U.S. Forest Service and the Works Progress Administration undertook an enormous public works project to stop the mass soil erosion taking hold during the Dust Bowl and bring back verdant, thriving American prairie land.

In one of the largest responses to an environmental crisis we've ever seen, between 1934 and 1942, some 220 million trees were planted from Canada to New Mexico.

Many of those trees still stand today, holding the healthy topsoil from blowing away with the prairie winds. But – they require upkeep and replacement to be as strong and beneficial as they were 80 years ago.

The Siksika Nation of Alberta, Canada, is heeding that call.

As they deal with dry and dusty prairie soils, mountain snows melting earlier, summers getting hotter, and river depths getting shallower – they decided to combat it by reviving a centuries-old practice to revitalize the land, hold back soil erosion, and fight climate change.

Working with government and community partners, the Siksika are preparing to plant 180,000 native seedlings for shelterbelts.

Example of a tree shelterbelt fortified by the addition of native plants.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Forest Service.

Extreme winds and more frequent, longer droughts have left the soil in poor condition, making it harder to grow crops to eat and sell. As the soil becomes drier and looser and gets picked up by strong winds, its carbon is released back into the atmosphere, ultimately contributing to a disastrous greenhouse gas cycle.

Growing native plants and trees will trap snow and retain moisture in the ground until spring arrives instead of blowing across the prairie. As the tree seedlings begin to take hold, other native plants with edible, medicinal, or cultural properties will be planted within the shelterbelts to increase biodiversity, grow food, and create animal habitat.

According to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, agriculture was Canada's fifth-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, accounting for 10% of the total. Strategically planted trees, shrubs, and other vegetation can nurse soils back to life while providing windbreaks, shelter, shade, food, wildlife habitat, and long-term carbon storage capacity.

As you dream of your spring gardens, remember: whenever and wherever we can, let's plant more trees!

Steady on,

Rob

Love your articles! Thanks for your content, Rob.

I grew up with shelter belts planted every mile along Kansas county roads, a reminder of the Dust Bowl.